I have spent most of my academic life explaining to people the complexities of immersive technologies, and Apple might make that effort more difficult because… marketing? AI is now a term that can mean everything, so much so that now can mean also nothing That is what I think Apple’s play is with the term ‘Spatial Computing’, which also can mean anything or nothing at this point.

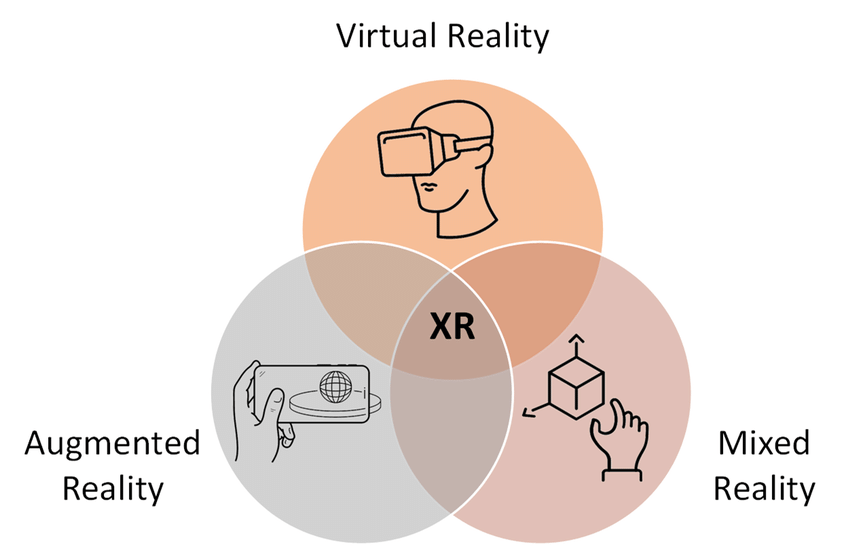

The terminology surrounding mixed reality (MR) and extended reality (XR) technologies has a rich and complex history in academia, deeply rooted in pioneering research and evolving concepts. One of the seminal works in this domain is the 1994 paper by Paul Milgram and Fumio Kishino, titled “A Taxonomy of Mixed Reality Visual Displays,” published in the IEICE Transactions on Information Systems. This groundbreaking study laid the foundation for understanding the spectrum of technologies that blend real and virtual worlds, a concept that has become central to what we now broadly term as XR, encompassing virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and MR.

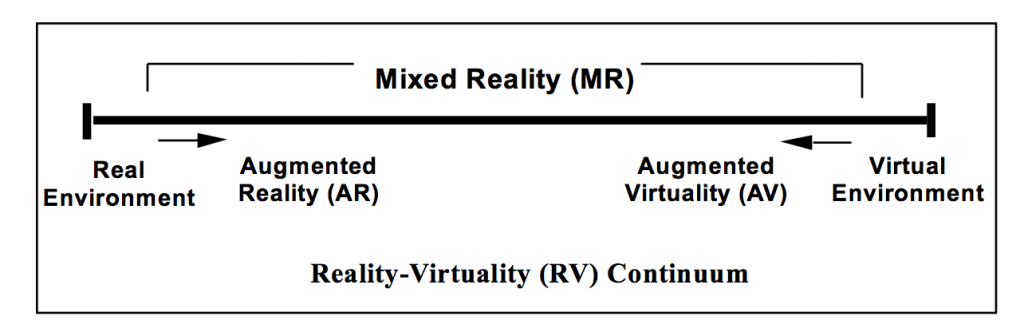

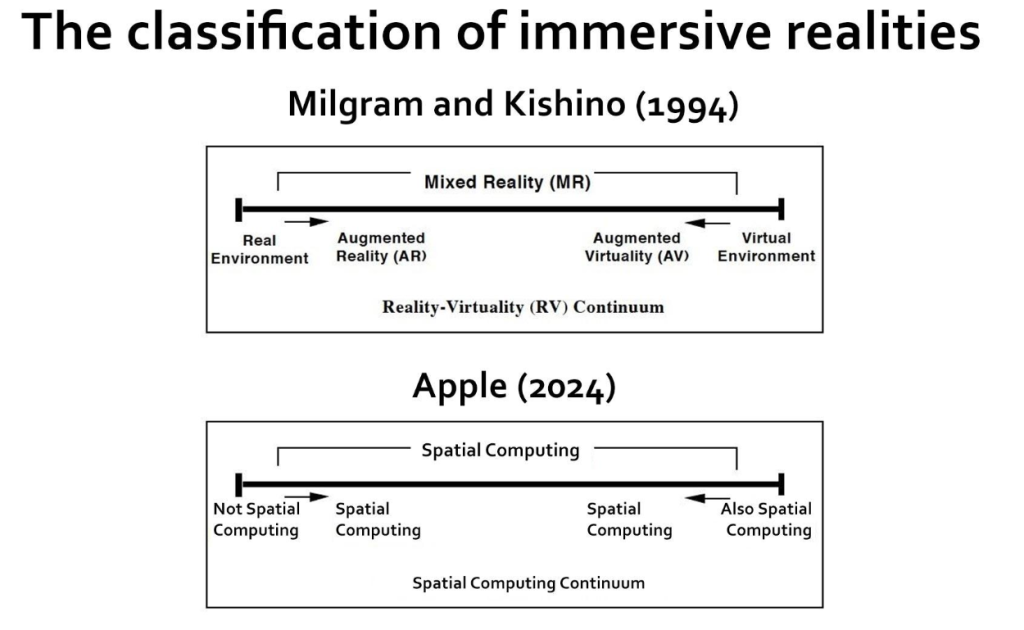

Milgram and Kishino introduced the influential concept of the “virtuality continuum,” which spans from completely real environments to entirely virtual ones. Within this continuum, they identified mixed reality as an intermediate state where real and virtual elements coexist and interact in real-time. This classification was instrumental in shaping the academic discourse around these technologies, distinguishing between various mixed reality forms such as AR, where the real environment is augmented with virtual elements, and augmented virtuality (AV), where virtual environments incorporate elements of the real world.

Further enriching the academic landscape, Milgram and Kishino’s work proposed a detailed three-dimensional taxonomy to classify MR systems, considering the Extent of World Knowledge (how much is known about the displayed world), Reproduction Fidelity (the realism of the display), and Extent of Presence Metaphor (the observer’s sense of presence in the virtual world). This framework provided a nuanced approach to understanding and categorizing the diverse range of MR technologies, from immersive VR experiences to AR applications that overlay digital information onto the physical world. This taxonomy not only clarified the terminology but also set the stage for future technological developments in the field.

The evolution of these terms and their interpretations reflect the dynamic nature of technological advancement and the ever-expanding boundaries of what is achievable in digital-physical integrations. The academic groundwork laid by researchers like Milgram and Kishino has been pivotal in guiding the industry’s trajectory, influencing how companies like Apple conceptualize and market their products, such as the Vision Pro. As these technologies continue to evolve, the foundational academic perspectives provide essential context for understanding and discussing the latest innovations in the field of spatial computing.

Origin of Spatial Computing

Like most origin stories, this one can be debated, as there are always new terms and spatial information systems or spatial learning predate the coining of ‘Spatial Computing’. The word spatial was used to help describe immersive technology as it was being first developed also, but most of the academic world latched onto the spectrum of reality above as it came with a more well defined concept. Similar concepts can be found in connection to geographic information systems (GIS) as far back as the 1960s.

Spatial Computing as a concept started appearing after Milgram and Kishino offered us the reality continuum concept in the late 1990s. The book “Spatial Computing: Issues in Vision, Multimedia and Visualization Technologies,” emerging from a specialized workshop, represents one of the earlier mentions of the term ‘Spatial Computing’ in an academic context. This publication brings together a diverse group of experts in fields such as computer vision, visualization, multimedia, and geographic information systems. The primary focus of the workshop, and consequently the book, was on integrating human perception and domain knowledge with the development of representations and solutions to complex problems involving the interpretation of sensed data. A key takeaway from this workshop was the recognition of the interconnectedness of various areas within spatial computing. The consensus underscored the importance of enhancing communication and collaboration across these fields to advance the understanding and application of spatial computing concepts. The book covers a wide range of topics, including Bayesian paradigms in image processing, robot navigation inspired by insects, object recognition, geometric variations, and the role of machine learning in image interpretation systems. It also delves into the challenges of visualizing complex spatial data and the conceptual representation for multimedia information. This early discussion and exploration of spatial computing highlight the multidisciplinary nature of the field and its relevance to a broad range of technological and scientific areas. The emphasis on human-centered approaches and the integration of domain-specific knowledge with computational methods set the groundwork for future advancements in spatial computing, influencing subsequent developments in areas like virtual and augmented reality.

The first compressive exploration of the term “spatial computing” first appeared in academic literature in the Master’s thesis of Simon Greenwold at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2003. Greenwold’s work, a blend of cultural criticism, theories of Human-Computer Interaction (HCI), and systems of mixed reality, explored the concept of spatial computing as a unique field of study. His thesis was pivotal in formalizing the idea of spatial computing and distinguishing it from related fields like 3D modeling and digital design.

Greenwold defined spatial computing as “human interaction with a machine in which the machine retains and manipulates referents to real objects and spaces.” This definition emphasized the importance of the physical world in the digital realm. Greenwold’s vision of spatial computing was not limited to three-dimensional representations but encompassed any computer-maintained space that appealed to human spatial perception, including two-dimensional surfaces like a piece of paper or interfaces like a desktop GUI.

The thesis discussed the historical context of machines in space, tracing back to mechanical devices like the abacus and early computers, which were inherently spatial in their operation. As technology advanced, and computers shrank in size, the emphasis shifted from the physical presence of these machines to their ability to represent and manipulate digital spaces. Greenwold argued that the ever-increasing power of computers to represent space internally led to the popularization of moving into virtual spaces. However, he cautioned against completely abandoning the physical aspect, advocating for a balance between the virtual and the real.

This perspective laid the groundwork for understanding spatial computing as a field that intertwines physical reality with digital enhancements, thereby paving the way for technologies we see today in XR and MR. Greenwold’s work marked a significant milestone in academic discourse, as it provided a framework for understanding how computational systems engage with real space and how this engagement differentiates spatial computing from purely synthetic virtual systems.

Apple’s Stance on the Terms

Apple’s approach to branding its new Vision Pro device is a strategic move that seeks to redefine and elevate the product beyond the conventional terminology of virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR). By opting for the term “spatial computing” instead of VR or AR, Apple is not only differentiating its product in a crowded market but also attempting to reshape the narrative around such technology.

The Vision Pro, as described, shares characteristics with both VR and AR. It blocks out the outside world like VR headsets, yet it employs world-facing cameras to present a clear representation of the user’s environment, integrating digital content into this space. This integration is more characteristic of AR technology. However, Apple’s choice to brand the Vision Pro as a “spatial computing” device rather than a mixed reality (MR) device—which could also be an apt description—allows the company to sidestep the established VR vs. AR debate. Instead, Apple focuses on a more descriptive and perhaps less confining term that encapsulates the Vision Pro’s capabilities more accurately.

This strategic branding is evident in Apple’s marketing and communication guidelines. The company has explicitly instructed developers to refer to their applications as “spatial computing apps,” avoiding the typical VR, AR, XR, or MR labels. This directive from Apple is not just about semantics; it’s a deliberate effort to create a new category and perception around the Vision Pro, setting it apart from other products in the market, including those in the burgeoning “metaverse” space led by companies like Meta.

Apple’s CEO, Tim Cook, has previously acknowledged the profound potential of AR technology, yet the company’s marketing materials for the Vision Pro deliberately avoid using VR/AR terms, aligning instead with the broader and more inclusive concept of spatial computing. This approach is characteristic of Apple’s history of redefining product categories and suggests an intention to position the Vision Pro not just as another headset in the AR/VR landscape but as a pioneer in a new domain of spatial computing.

The challenge for Apple, however, lies in popularizing this new category. With a high price tag and an appearance similar to niche VR headsets, the Vision Pro’s success hinges on Apple’s ability to convey its unique value proposition to a mainstream audience. The company’s promotional efforts, reminiscent of the original iPhone’s introduction, indicate a push to herald the Vision Pro as a paradigm shift in technology. Integrating AI into the mix could further enhance the device’s appeal, positioning it as a vanguard for the convergence of spatial computing and artificial intelligence.

In summary, Apple’s decision to label the Vision Pro as a spatial computing device is a calculated move to establish a new product category, one that transcends existing VR and AR frameworks and aligns with the company’s history of innovation and market influence.

Microsoft’s ‘Mixed-Reality’ Headsets

The situation with Microsoft’s Mixed Reality platform exemplifies a broader industry trend where the terms ‘virtual reality’ (VR), ‘augmented reality’ (AR), and ‘mixed reality’ (MR) are sometimes used interchangeably or inaccurately, despite having distinct definitions in academic and research contexts. Introduced in 2017, Windows Mixed Reality was Microsoft’s foray into the immersive technology space, positioned as a competitor to VR giants like HTC and Oculus (now owned by Meta). Marketed under the ‘Mixed Reality’ banner, the platform and its associated headsets, produced by partners such as Acer, Dell, Lenovo, Asus, HP, and Samsung, were largely VR-centric in functionality, providing immersive VR experiences focused on gaming, apps, and virtual environments.

This misalignment in terminology, where Microsoft’s products were labeled ‘Mixed Reality’ but functioned more like VR headsets, may have led to confusion among consumers. The term ‘Mixed Reality’, as established in academic circles, particularly through seminal works like that of Paul Milgram and Fumio Kishino, refers to a blend of real and virtual worlds where physical and digital objects coexist and interact in real-time. However, the headsets associated with Windows Mixed Reality did not fully embody this MR concept and were more aligned with VR technology, offering immersive experiences largely disconnected from the physical world.

The recent announcement of the discontinuation of Windows Mixed Reality, along with the accompanying Mixed Reality Portal app and Windows Mixed Reality for Steam VR, marks a significant moment in the tech industry. Microsoft stated that Windows Mixed Reality is “deprecated and will be removed in a future release of Windows.” Despite this, Microsoft continues to focus on other applications of VR, such as its Microsoft Mesh app that will soon let co-workers meet in a virtual space without a headset. It also started letting Quest users access Office apps and its Xbox Cloud Gaming platform through a partnership with Meta. This shift and the continued development of the HoloLens, which aligns more accurately with the MR definition, suggest a strategic realignment by Microsoft.

The deprecation of Windows Mixed Reality underscores the complexities and challenges in aligning marketing strategies with established academic and technical definitions. For consumers and industry stakeholders, this serves as a reminder of the importance of understanding the nuances of these technologies. As the immersive technology landscape continues to evolve, clarity in terminology will be crucial for consumer understanding and informed decision-making in this rapidly advancing field.

Effect on our Research

The rebranding and introduction of new terminology by major tech companies like Apple can significantly impact the efforts of organizations like the Mixed, Augmented, and Virtual Realities Special Interest Group (MAVR), which operates under the Japan Association for Language Teaching (JALT). These impacts can be both challenging and opportunistic in nature, affecting how MAVR educates the public about immersive technologies in teaching and learning.

Challenges:

- Shifting Terminology: As Apple and other tech giants introduce terms like “spatial computing,” MAVR may face challenges in aligning its educational content with the evolving nomenclature. This could lead to confusion among the general public and educators who look to MAVR for guidance. Keeping up with industry jargon while maintaining consistency in educational material becomes a balancing act.

- Commercial Influence: Apple’s branding strategy could skew public perception and understanding of these technologies, potentially overshadowing the more nuanced differences between VR, AR, and MR as understood in academic and research circles. This shift might challenge MAVR’s mission to provide a rational and fair-minded counterpoint to commercial narratives.

- Technology Adoption and Awareness: Apple’s marketing reach and influence could redefine expectations and understanding of immersive technologies among the general public. This could necessitate adjustments in MAVR’s approach to educating its audience, especially if spatial computing becomes a dominant term.

Looking into the Future

The introduction of Apple’s Vision Pro and its emphasis on ‘spatial computing’ as opposed to established VR/AR terms is not the first instance where marketing strategies have deviated from established industry terms, leading to some confusion and challenges among consumers and developers. This is reminiscent of Microsoft’s earlier approach with its ‘Mixed Reality’ headsets, which were essentially VR headsets but marketed under the mixed reality banner. Apple’s Vision Pro, much like the Windows Mixed Reality platform, is faced with the challenge of defining its unique place in the market and ensuring developer and consumer buy-in. Interestingly, Apple seems to be banking on the web, particularly its Safari browser, as a crucial application for the Vision Pro. This approach is indicative of a broader shift back to the open web, where the utility of the device might largely hinge on web-based applications rather than native apps specifically designed for the platform.

One significant challenge that Apple faces in promoting its Vision Pro as a revolutionary device is its ongoing disputes over how the App Store operates, particularly with regards to revenue sharing and the restrictions on transactions outside the App ecosystem. This friction has led to high-profile companies like Netflix, Spotify, and YouTube resisting native app development for the Vision Pro. Apple’s insistence on commissions from in-app purchases and subscriptions, even those acquired through external web links, exacerbates this tension with developers. In this context, the web becomes not just a workaround but a potential key driver for the Vision Pro’s utility. Users might access services like Spotify or YouTube not through native apps but via their web versions. This shift could signal a return to a more URL-centric, browser-based interaction model, reversing a trend where mobile and immersive platforms have focused on app-centric experiences.

Apple’s Vision Pro and its reliance on the web as a key application highlight the ongoing tensions between established market practices and emerging technological paradigms. This scenario mirrors past instances where marketing strategies have not aligned with academic or industry-standard terminologies, posing both challenges and opportunities for the future of immersive technology platforms.

About the Author

Eric Hawkinson

Learning Futurist

Eric is a learning futurist, tinkering with and designing technologies that may better inform the future of teaching and learning. Eric’s projects have included augmented tourism rallies, AR community art exhibitions, mixed reality escape rooms, and other experiments in immersive technology.

Roles

Professor – Kyoto University of Foreign Studies

Research Coordinator – MAVR Research Group

Founder – Together Learning

Developer – Reality Labo

Community Leader – Team Teachers